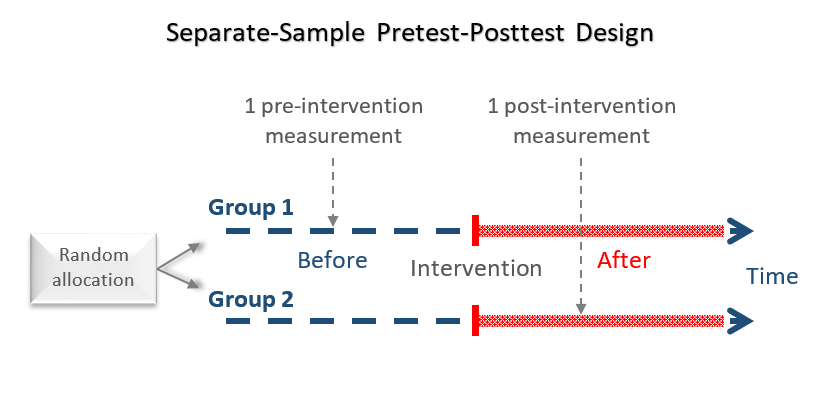

The separate-sample pretest-posttest design is a type of quasi-experiment where the outcome of interest is measured 2 times: once before and once after an intervention, each time on a separate group of randomly chosen participants.

The difference between the pretest and posttest measures will estimate the intervention’s effect on the outcome.

The intervention can be:

- A medical treatment

- A training or an exposure to some factor

- A policy change, etc.

Characteristics of the separate-sample pretest-posttest design:

- Data from the pretest and posttest come from different groups.

- Participants are randomly assigned to each group (which makes the outcome of the pretest and posttest comparable).

- All study participants receive the intervention (i.e. there is no control group).

Although there is an element of randomness associated with this design, it is still considered a quasi-experiment. This is because, unlike a true experiment, participants are not randomly chosen to either receive the treatment or not, instead, they are only randomly assigned to either get the pretest (group 1) or the posttest (group 2). So all participants are still getting the intervention in a natural and non-random way (e.g. according to their choosing or that of the researcher). Therefore, the researcher here is controlling who gets measured and when, versus in a true experiment where the researcher controls who gets the intervention and when.

Advantages of the separate-sample pretest-posttest design:

The benefit of using a separate-sample pretest-posttest design is that it avoids some of the most common biases that other quasi-experimental designs suffer from.

Here are some of these advantages:

1. Avoids testing bias

Definition: Testing effect is the influence of the pretest itself on the posttest (regardless of the intervention). Testing bias can happen when the mood, experience, or awareness of the participants taking the pretest is affected, which in turn will affect their posttest outcome.

Example: Asking people about a psychological or family problem in a pretest may affect their mood in a way that influences the posttest. Or when the response rate of the posttest declines after taking a long and time-consuming pretest.

How it is avoided: Perhaps the biggest advantage of using a separate-sample design is that the pretest cannot affect the posttest, since different groups of participants are measured each time.

2. Avoids regression to the mean

Definition: Regression to the mean happens when participants are included in the study based on their extreme pretest scores. The problem will be that their posttest measurement will naturally become less extreme, an effect that can be mistaken for that of the intervention.

Example: Some of the top 10 scorers on a first round in a sport competition will most likely lose their top 10 ranking in the second round, because their performance will naturally regress towards the mean. In simple terms, an extreme score is hard to sustain over time.

How it is avoided: Since the posttest participants are not the same as those measured on the pretest, this rules out their inclusion in the study based on their unusual pretest scores, therefore avoiding the regression problem.

3. Avoids selection bias

Definition: Selection bias happens when compared groups are not similar regarding some basic characteristics, which can offer an alternative explanation of the outcome, and therefore bias the relationship between the intervention and the outcome.

Example: If participants who were less interested in receiving the intervention were somehow more prevalent in the pretest compared to the posttest group, then the outcome of the posttest and the pretest cannot be compared anymore because of selection bias.

How it is avoided: In a separate-sample pretest-posttest design, selection bias can be ruled out as an explanation since the 2 groups were made comparable through randomization.

4. Avoids follow-up

Definition: Loss to follow-up can cause serious problems if participants who were lost to follow-up differ in some important characteristics from those who stayed in the study.

Example: In studies where participants are followed over time, those who did not feel any improvement may not return to follow-up, and therefore the effect of the intervention will be biased high.

How it is avoided: Separate-sample pretest-posttest studies are protected against such effect as each group must be measured only once, and therefore there is no follow-up of participants over time.

Limitations of the separate-sample pretest-posttest design:

For each limitation below, we will discuss how it threats the validity of the study, as well as how to control it by manipulating the design (adding or changing the timing of observations). Statistical techniques can be used to control these limitations, but these will not be discussed here.

1. History

Definition: History refers to any event other than the intervention that takes place between the pretest and the posttest and has the potential to affect the outcome of the posttest, therefore biasing the study.

Example: When studying the effect of a medical intervention on weight loss, an outside event such as the launch of a documentary that has the potential to change the diet of the study participants can co-occur with the intervention, and become a source of bias.

How to control it: If the resources are available, repeating the study 2 or more times at different time periods makes History less likely to bias the study, as it would be highly unlikely that every time a biasing event will occur.

2. Maturation

Definition: Maturation is any natural or biological trend that can offer an alternative explanation of the outcome other than the intervention.

Example: Participants growing older in the time period between the pretest and posttest may offer an alternative explanation to an intervention for smoking cessation.

How to control it: Adding another pretest measurement can expose natural trends and thus control for maturation.

3. Mortality

Definition: When the pretest and posttest are separated by a long time period, some participants may become unavailable for the posttest when the time comes. If those differ systematically from those who are still available for the posttest, then the pretest and posttest groups that are no longer comparable.

Example: Over time, patients who become severely sick from a certain medical condition are more likely to be hospitalized and therefore become unavailable for the posttest, creating a source of bias.

How to control it: Taking an additional posttest measurement of the group who received the pretest will eliminate Mortality effects as it provides a measurement of the same type of participants available for the posttest.

4. Instrumentation

Definition: Instrumentation effect refers to changes in the measuring instrument that may account for the observed difference between pretest and posttest results. Note that sometimes the measuring instrument is the researchers themselves who are recording the outcome.

Example: Using 2 interviewers, one for the pretest and another one for the posttest may introduce instrumentation bias as they may have different levels of interest, or different measuring skills that can affect the outcome of interest.

How to control it: Use a group of interviewers randomly assigned to participants.

Finally, adding a control group to the separate-sample pretest-posttest design is highly recommended when possible, as it controls for History, Maturation, Mortality, and Instrumentation at the same time.

Example of a study that used the separate-sample pretest-posttest design:

Lynch and Johnson used a separate-sample pretest-posttest design to evaluate the effect of an educational seminar on 24 medical residents regarding practice-management issues.

A questionnaire that assesses the residents’ knowledge on the subject was used as a pre- and posttest.

The advantages of using a separate-sample pretest-posttest design in this case were:

- Ease of feasibility: Since the questionnaire was time-consuming, giving participants the opportunity to be tested just once was important to get a high response rate (in this case 80%).

- The testing effect was controlled: The participants’ familiarity with the questions asked in the pretest did not affect the posttest.

The study concluded that there was a statistically significant improvement of the knowledge of residents after the seminar.

References

- Campbell DT, Stanley JC. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research. Wadsworth; 1963.